Disaster Management and Resilience in Healthcare

Read the Magazine in PDF

Abstract

This article explores resilience, complexity thinking, disaster management, and healthcare systems. It emphasizes the importance of resilience in healthcare systems and the need to prioritize public health in pandemic responses. The Resilience Assessment Guide is recommended as a tool for disaster management. Two studies are discussed: an international survey on COVID-19 measures taken by different countries and the 40HS, C-19 study, which highlights the significance of broad-based testing in managing the pandemic. The findings indicate that early stringency measures and pre-existing government capacity alone are insufficient for effective pandemic management.

Introduction

Resilience

Resilience involves preventing and mitigating crises, adjusting before, during, and after disturbances, and maintaining effective function despite pressure. It is vital in the current COVID-19 era when health systems face significant strain. Resilience requires adaptability, responsiveness, learning, improvisation, flexibility, and maneuverability. A resilient system is intrinsic to an organization, enabling it to function despite challenges. Assessing your system’s resilience according to this definition is crucial. [1]

Complexity Science and Complexity Thinking

Healthcare systems are complex and cannot be simplified into linear cause-and-effect models. Unlike other systems, issuing policies or presenting new studies cannot easily fix healthcare. It is a complex adaptive system, not a linear one. Acknowledging this complexity is crucial when aiming for changes and improvements in healthcare. [2]

Fukushima: Triple Disaster

The Japanese case of Fukushima exemplifies resilient healthcare and disaster management. A decade ago, a great earthquake caused a tsunami, leading to a nuclear plant meltdown. The triple disaster resulted in loss of life, displacement, economic consequences, and ongoing environmental issues. Despite efforts, challenges persist, and only a few people have returned home. Restoring Fukushima and the nuclear reactors remains a significant task. Japan faces the challenge of balancing power needs with environmental concerns, just like India, which strives for reliable power while transitioning to renewables gradually.[3]

Spanish Flu

Approximately a hundred years ago, the Spanish flu pandemic struck, infecting around 500 million people and causing 50 million deaths.

Medical knowledge and capabilities were limited compared to today. Diseases and viruses were poorly understood, and there were no reliable testing methods, vaccines, antibiotics, or antivirals. Access to medical care was also limited, and many doctors operated independently. [4]

After the Spanish flu, some countries embraced alternative medicine while others continued to prioritize scientific methods. Over the last century, improvements in disease surveillance, data collection, and public health decision-making occurred. Today, the crucial question is whether we will prioritize public health in battling pandemics like COVID-19. After the Spanish flu, some countries forgot this priority, leading to a lack of universal healthcare and increased vulnerability to pandemics.

The World Health Organization advocates for universal healthcare coverage as a critical tool in pandemic prevention [5].

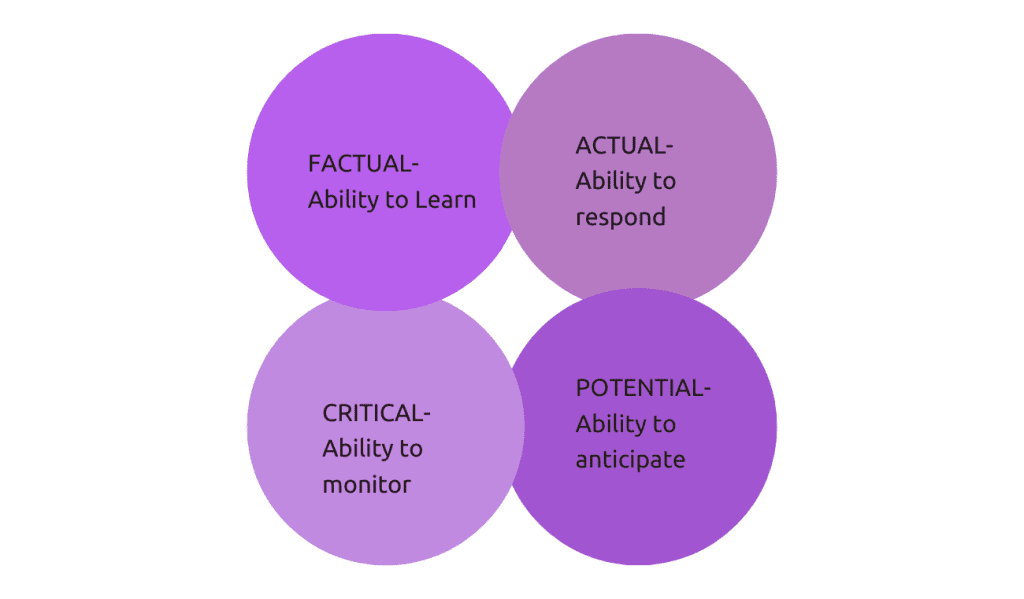

Thunderstorm Asthma

The Thunderstorm Asthma event in Melbourne, Australia 2016 highlighted the importance of disaster management tools like the Resilience Assessment Guide. This guide emphasizes four essential capacities for any disaster system: learning before and during the crisis, rapid response, anticipation of future events, and continuous monitoring. The event involved nearly 10,000 people experiencing breathing difficulties due to an unusual combination of weather factors. [6]

During this period in Australia, there were daily admissions to intensive care, and on November 26th, there was a significant spike in these admissions.[7]

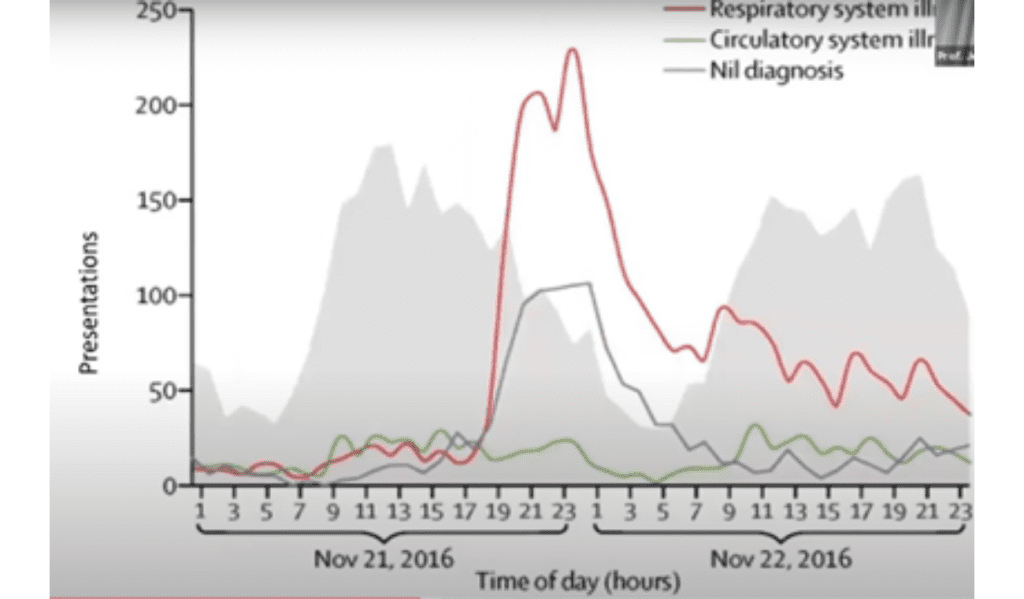

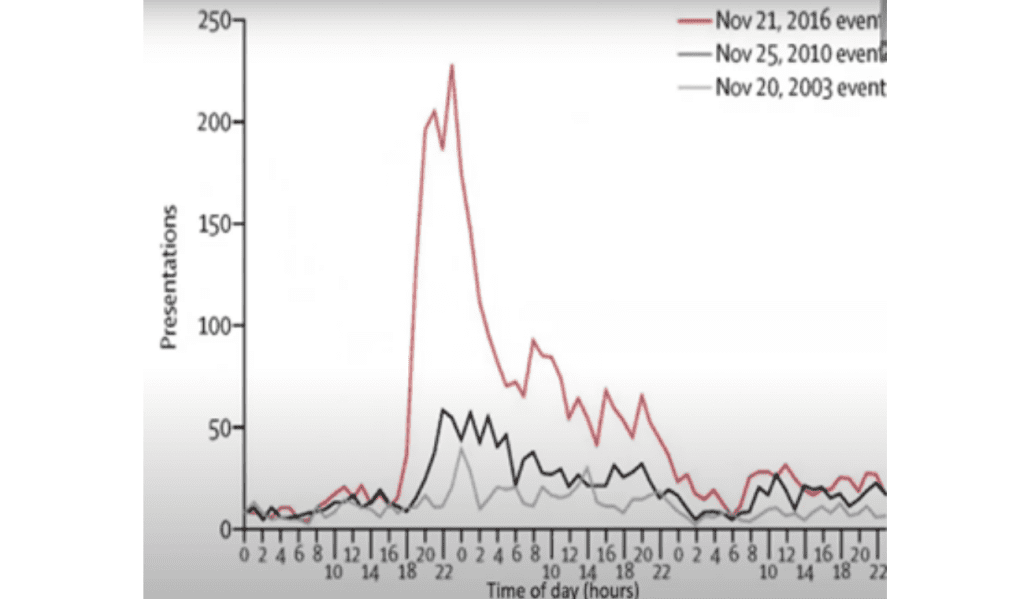

Here you can see a huge spike in callouts at a particular time of the day.

In Melbourne and Geelong hospitals in Victoria, Australia, there were hourly presentations to emergency departments, and there was a noticeable spike in these presentations during the mentioned period.

The age and sex distribution of these presentations show that young boys were affected the most, resulting in a significant number of admissions.

Subsequently, many admissions from men and women in their middle years were affected by asthma and had to rush to the emergency department.

Here is an analysis of the hourly respiratory presentations to the emergency departments of Victoria’s public hospitals using the resilience grid.

In the unfolding disaster, there was no initial anticipation due to its unexpected nature. However, communication across the health system improved, and response capacity increased to manage the surge in demand. Learning during and after the event was crucial for future preparedness. The Australian bushfires, with their similarities to India’s climate and susceptibility to such disasters, serve as another instructive case. [8]

Bushfires

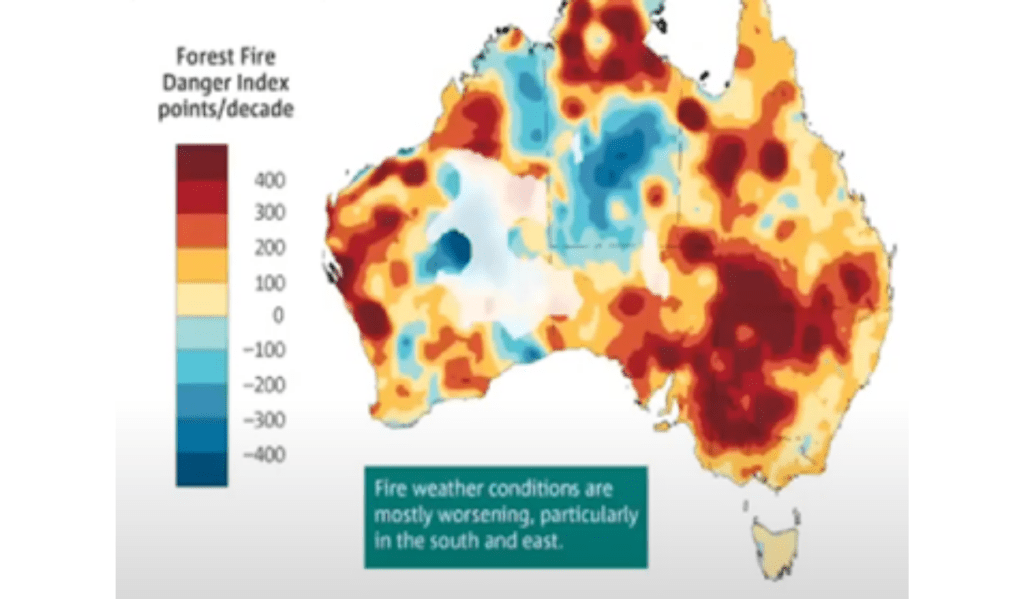

Around a year and a half ago, Australia experienced its worst bushfires, exacerbated by climate change with dry winters and increased temperatures. The fires burned 19.4 million hectares of land, surpassing other notable fires globally. The impact was significant, with many homes destroyed, the economy affected, and an estimated billion animals perishing, putting entire species at risk. Climate change, leading to declining rainfall and prolonged drought, played a substantial role. The danger index is expanding in high-risk areas, including Southeast Asia, Africa, and India.[9]

COVID-19

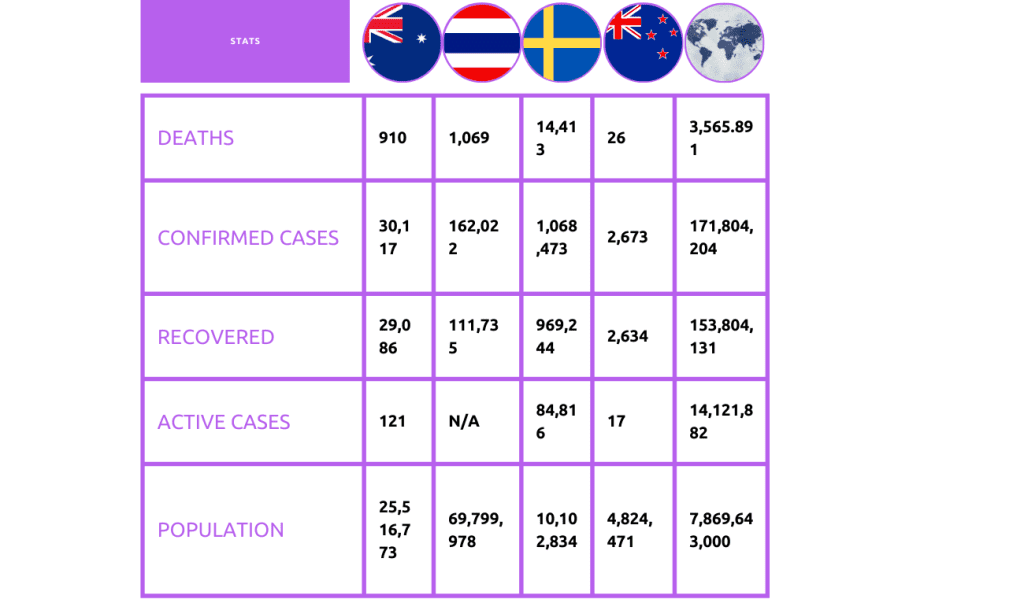

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, let’s look at brief case studies of four countries: Australia, Thailand, Sweden, and New Zealand. Australia, a high-income country with 25 million people, implemented a national approach with measures like establishing a national cabinet, funding telehealth, and redirecting services. Thailand, a middle-income country with 70 million people, trained health force volunteers to educate on hand hygiene and physical distancing.

Sweden, a high-income country with 10 million people, took a different approach without mandatory mask-wearing or physical distancing, relying on common sense. New Zealand, a relatively small country, aimed for complete suppression and elimination of COVID-19, succeeding in this approach.

COVID-19

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, let’s look at brief case studies of four countries: Australia, Thailand, Sweden, and New Zealand. Australia, a high-income country with 25 million people, implemented a national approach with measures like establishing a national cabinet, funding telehealth, and redirecting services. Thailand, a middle-income country with 70 million people, trained health force volunteers to educate on hand hygiene and physical distancing.

Sweden, a high-income country with 10 million people, took a different approach without mandatory mask-wearing or physical distancing, relying on common sense. New Zealand, a relatively small country, aimed for complete suppression and elimination of COVID-19, succeeding in this approach.

Study 1: “International Survey of COVID-19 Management Strategies”

A cross-sectional online survey gathered opinions from 1131 healthcare staff in 97 countries on COVID-19 response. Regional differences in pandemic strategies were observed. Progress has been made, but improvements are needed in widespread testing and social control measures. [10]

Study 2: “The 40 Health Systems, COVID-19 (40HS, C-19) Study”

Examined data from 40 national health systems on government capacity, response stringency, testing, and outcomes.

Early stringency measures and broad-based testing were associated with lower cumulative deaths, while late stringency measures and narrow testing had poorer outcomes. Pre-existing government capacity alone was insufficient in managing COVID-19 effectively. [11]

The danger index reveals expanding red areas (high danger) and decreasing blue areas (safer regions) across many regions, including Southeast Asia, Africa, and India. A study used color-coded maps to rank countries based on response capacity, testing breadth, and timing of stringency measures during the crisis. Learning from COVID-19 experiences, the question remains: can we predict and respond to future crises more effectively? Resilient disaster management and robust health systems in some countries offer hope for coping with future crises.

What is the “new normal”?

The “new normal” describes changes in response to COVID-19, with hope for a stronger future through improved health systems and disaster preparedness. Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organisation, emphasizes that returning to the old normal is insufficient, and the new normal requires continued measures like physical distancing, testing, and tracing. Climate change also demands attention for long-term resilience.

Colombia’s use of scientific approaches for government assistance indicates the potential for the future, and applying new ideas is crucial for preparing for future crises. [12]

Conclusion

Healthcare systems require a complex adaptive system approach for improvement and resilience. Learning from past events like the Spanish flu and Fukushima is vital for prioritizing public health. The Resilience Assessment Guide’s four capacities are crucial for disaster response. Acknowledging healthcare complexity is essential for making changes and building resilience in organizations. Universal healthcare coverage is a critical tool for pandemic prevention.

References

- The 40 health systems, COVID-19 (40HS, C-19) study. (2021, February 20). PubMed.

- Complexity Science in Healthcare: Aspirations, Approaches, Applications and Accomplishments – A White Paper. (2017, March 31). Macquarie University.

- Hollnagel, E., Pariès, J., & Wreathall, J. (n.d.). Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook – 1st Edition – Erik H. Routledge. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

Author

-

President ISQua, Founding Director Australian Institute of Health Innovation (AIHI); Director, Centre for Healthcare Resilience and Implementation Science(CHRIS); Professor, Health Systems Research, Macquarie University Sydney, Australia