Coproducing Healthcare Services

Read the Magazine in PDF

Abstract

This article explores healthcare service improvements through co-production, involving patients and professionals to create a tailored delivery system. Integrating patient-centered care, evidence-based practices, and cost-effectiveness enhances care comprehensively. Co-production emphasizes relationship building, professional preparation, education design, and involving patients for safer healthcare. Although attitude changes may take time, taking co-production seriously is vital for advancing healthcare services.

Introduction

The topic aims to enhance healthcare service value and health outcomes. Co-producing services, considering patients’ and professionals’ perspectives, fosters collaboration. A service-oriented approach prioritizing patient needs over a product-oriented one is crucial. Understanding contextual forces and incorporating social experiences alongside scientific knowledge is essential for improving healthcare delivery.

We are learning

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of collaboration, innovation, and control in healthcare delivery. Health inequities persisted, emphasizing the need to honour patients’ and professionals’ personhood and build a system based on mutual respect, trust, shared learning, and patient-centred care.

A century ago, identifying a good hospital led to established standards, but the focus shifted to include even some peripheral matters over time. Healthcare providers sought improvement through enterprise-wide systems, understanding processes, relationships, and performance measurement. However, recently a new perspective emerged, recognizing the need for co-produced healthcare services, integrating multiple knowledge systems.

Not 1.0vs 2.0vs 3.0; Rather 1.0+2.0+3.0

Recently, the approach has shifted towards combining patient-centred care and evidence-based practices to achieve measurable outcomes. Value in healthcare is not solely based on results but also on patient experience and cost-effectiveness. The co-production concept introduced by Victor Fuchs highlighted the role of providers and consumers in creating a service. However, applying product-making logic to services distorted our understanding of service marketing.

Researchers like Victor Fuchs and Eleanor Ostrom contributed to the concept of co-production, while Stephen Vargo and Robert Lush argued that product-dominant logic overshadowed service-dominant marketing. Therefore, creating a successful healthcare system requires collaboration, patient-centeredness, and a shift in understanding healthcare as a co-produced service. By combining evidence-based practices, patient needs, and cost-effectiveness, we can develop a comprehensive and effective model of care that benefits society as a whole.

Health Care Service

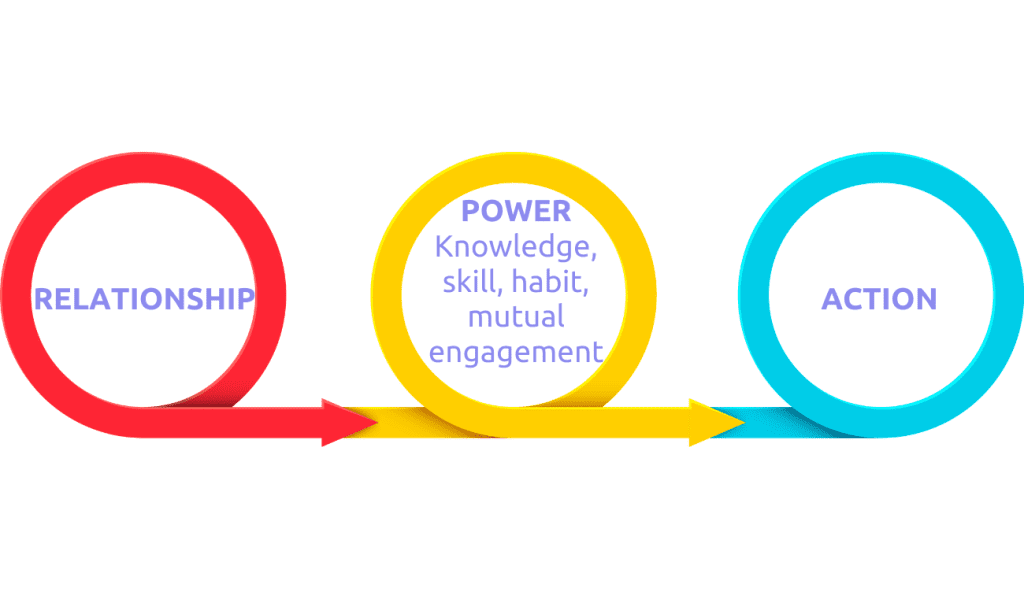

Healthcare services involve relationships and actions linked by shared knowledge, skills, habits, power, vulnerability, and engagement. The underlying power dynamics can distort the service, necessitating consideration of all three components’ interactions in healthcare improvement. Collaboration between parties, whether on an individual or macrosystem level, is essential in creating services and acknowledging the influence of power dynamics and hierarchies. Nevertheless, ancient wisdom calling attention to crucial underlying kinship relations remains relevant in this process.

The ancient Hindu traditional knowledge of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbukum” recognizes our kinship relations. However, the inquiry is focused on understanding the underlying drivers that enable the co-production of healthcare services. There are three knowledge streams involved in co-producing healthcare servic knoKledge streams involved in co-producing healthcare services.es.

- The first two relate to the patient’s and professional’s lived realities, social support, and resource access.

- The third stream is knowledge of the system, including the journey to be navigated and its associated emotions.

- The fourth stream is science-informed practice, which includes not just the science of the disease or condition but also the illness experience and service design.

Including professionals in the process is crucial, as seen in “Intelligent Kindness” by John Ballatt’s team in the UK. If we imagine a pair of glasses with two lenses, one focusing on kinship and the other the task, we can see how the two knowledge streams are woven together in a service-making logic guided by skill, habit, and vulnerability.

Meaningful relationships are vital to co-pMeaningful relationships are vital in co-producing healthcare services, an understanding rooted in ancient folk wisdom. Knowledge, skill, habit, and a willingness to be vulnerable connects relationships and activities. The science informing our understanding of disease biology differs from the knowledge systems of the illness experience and service design, necessitating learning and unlearning. Combining self-care and professional support, well-functioning systems are essential for healthcare services. Using task and kin lenses can bring fresh insights. Co- production’s complex service-making logic offers lessons for understanding the service-dominant logic perspective.

Øystein Fjeldstad, from Norway, significantly influences the thinking on service improvement. He suggested a different architecture for systems that solve problems rather than those that produce products. This architecture can occur at individual and population levels as a “shop” or a “network.” The logic or architecture of problem-solving systems differs from that of product-making systems, which follow a value chain of standardised sequential processes. While the idea was intriguing, it was initially problematic to see how it could be applied concretely.

Øystein Fjeldstad works in Norway. Together we have studied a dialysis unit in Sweden. The team has different rooms for patients undergoing dialysis:

- A space for individual patients needing customized, redesigned dialysis

- A room with many patients being dialyzed by nurses according to pre-set algorithms,

- Three rooms where patients do their hemodialysis and interact with each other.

Patrick, a former patient, manages the equipment and spaces, while Nils Johan, the nephrologist, oversees the entire system. This unit exemplified the value shop, the value chain and the value network, where individual and population-level services are provided, respectively. This service architecture could be used in healthcare. Other examples exist in learning health systems, networks, and individual settings.

Coproduced Healthcare Service

The co-production of healthcare services has significant implications:

- One’s health cannot be outsourced to a professional, so professional preparation, education design, system leadership development, and integrative thinking all help prepare people for co-producing healthcare services.

- Clinical practice knowledge can be developed by studies of people in large groups and as individuals, akin to what we see in modern genomics.

- Actively involving patients and families can enhance safety in healthcare services.

- Healthcare service safety is not simply “safe” or “unsafe.” Continuous efforts are needed to make services “safer

Disease registers are evolving into learning networks and teams, enabling new value-creation approaches. Understanding co-produced healthcare services involves considering differences in “service making” vs. “product making,” emphasizing relationships, scientific methods for knowledge building, and the streams of knowledge, skill, and habit. Personal experiences in co-production offer valuable insights.

The questions that are being considered might be interesting. These are:

- How does service-making differ from product-making?

- Why are relationships crucial for health, and is this a new concept?

- How are the scientific methods for building knowledge of diseases different from the inside experience of being ill, having an illness, or designing and assessing a service?

4. What are the knowledge, skill, and habit streams that help co-produce a healthcare service? When have you experienced the co-production of a healthcare service?

Seeing each other as people when interacting with patients is crucial, but some patients may still prefer a product-focused approach. Changing attitudes will take time due to ingrained thinking, but taking co-production seriously is vital to begin the shift.

Conclusion

Enhancing healthcare service value entails a shift to co-production, recognizing patient and professional realities of daily life, and fostering collaboration. Prioritize patient needs, combining evidence-based practices and patient-centred care. The approach includes patient and professional knowledge streams, social support, resource access, system understanding, emotions, and science-informed training. Co-production integrates multiple knowledge systems, inviting new value architectures to improve science-informed practice.

FAQs

Q: What is the difference between service and product making, and why is it important to consider in healthcare?

A: The logic of making a product is linear, which may not always be the healthcare case. Patient-person conversations revealed that professional names for steps were not always the same as patient-given names, and both parties contributed along the way. As a result, service-making is different from product-making, and a different approach is necessary to work together to meet the needs of patients.

Q: Do you see any logistic or practical problems at the ground level, especially when making health care affordable and accessible?

A: The author believes there are time-consuming and time-saving approaches to making healthcare affordable and accessible. One example is a gastroenterologist who asked patients to answer his questions ahead of time and enter them in a text message to send back to him. This allowed him to focus on what mattered most to the patient during the session rather than spending time asking routine questions.

Q: Will this approach be more time-consuming for reclamation?

A: The author explains that there are ways to make the process more time-consuming or less time-consuming, depending on the approach. The example of the gastroenterologist mentioned earlier saved time by having patients answer questions beforehand, allowing for more focused sessions.

Q: Do insurance companies like converting healthcare services into products?

A: The author states that insurance companies love the idea of converting healthcare services into products. However, the author believes there are better ideas than relying on financing mechanisms to be the authors of innovation in healthcare.

Author

-

Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice