Person-centred care & its principles

Read as Magazine PDF

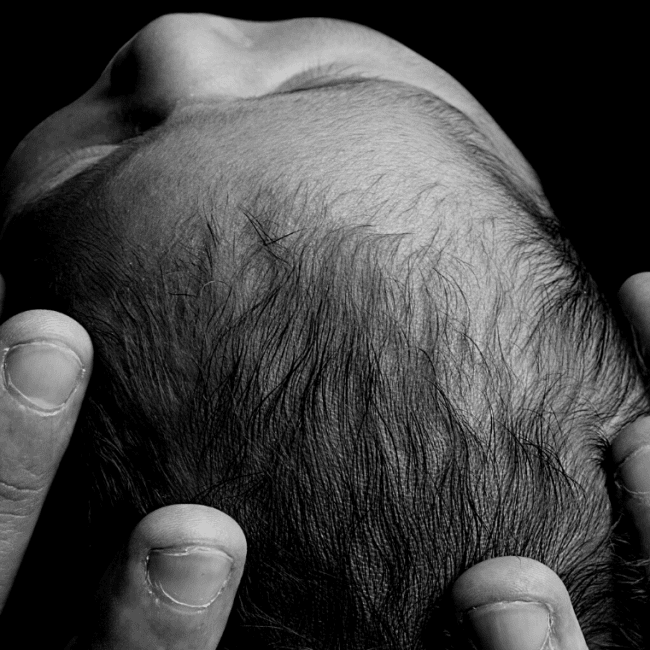

think stories are a great way of communicating why something is important. So this is a story of Robert that's been published. It's anonymized, of course, by some authors that have looked into the story of a person who is HIV positive and has dropped out of his anti-retroviral therapy program or art program. And as most of you probably know, ART is a lifelong treatment. And if you drop out of your treatment program, you're actually at risk of dying of AIDS. So both the care system and the patient need to follow up and follow through on the ART program. Yet up to one-third of HIV patients are lost to follow up, even when care or the treatment program is free of charge.

Robert’s story is just one of many, but it illustrates some of the challenges that healthcare systems have. And I want to underline that in this work, we’ve seen that anywhere where modern medicine has taken hold, we see the same challenges. They exist all over the world. It is not any better in any part of the world as far as we can see it.

Robert says, about why he dropped out of his ART. He said, “You know, sometimes it’s difficult to get vehicles. And when you go to look for money for a motorcycle or a taxi, you find you don’t have it. So when you miss your appointment and go to the clinic, then another day the provider starts calling you about not having come on the appointed day. And we tell that person that you got problems. He tells you you should have spent the night on the road. So how can I spend the night on the road here? I have failed to get money for taking

me to the hospital. And then I’m supposed to get money to spend the night somewhere and feed myself. These are some of the problems I have in going to the clinic. Now, the researcher doesn’t give up that easy and says challenges, Roberts says. But still, why didn’t you come back despite what happened to you? I mean, this is important. You should have come back to the clinic and met with some other health professional. And I told her, no, I didn’t want to show up because what happened to me was still in my heart. If I had been treated nicely, the situation would have been different. I was treated badly. I saw the treatment was meaningless.”

And so this is an illustration of a person that feels disrespected by some professionals in a care system, probably a stressed-out professional who had many good reasons to be and to snap. And yet it has this devastating consequence for this person who just feels he can’t take it anymore.

This is easy to sympathize with and empathize with. We shouldn’t have situations like this, and yet we have data that shows that abuse or mistreatment of patients happens all over the world. Here is a qualitative study that’s been published in PLOS Medicine, which is a systematic review of 65 studies from 34 countries exploring the experiences of women who give birth in health care facilities and the reports of abuse that arrive here are quite astounding. And so this is a system challenge, and it’s a system challenge that goes across all over the world. 90% of women in maternity wards report that 90% of the providers or 90% of the women report that the providers never introduced themselves and that providers never asked permission before performing medical procedures.

Here is an example from my own country. She’s a little bit more she explains a little bit more how she sees the healthcare system from both sides because this person has worked as a nurse as many for many years in the public healthcare system. And now she is a cancer patient interface fifties, and she writes a letter to her oncology department and she says, Now, I feel like I’m put on the sideline having to fight two battlefields at the same time against the system and cancer. I’m afraid our next meeting will not allow the time or the possibility of discussing anything but medical and technical things. I’m afraid of being seen as difficult and making incessant complaints, afraid of not getting a chance to express myself and have real inter-human contact.

We can maybe summarize the challenge like this, health care is not able to, for some reason, pay sufficient respect to the individuality and human dignity of the persons who seek help from them. And there seems to be a conflict – a tension between providing excellent technical care and being able to be connected and empathic and sympathetic towards the person who is seeking care from us. This shows the importance of person-centred care.

I hope that these stories speak to hearts that we should be able to provide both sympathetic person-centred care and excellent technical care. There is no tension, really, between them. So if we want to deliver person-centred care, we have to know what is front and centre.

WHAT IS PERSON-CENTRED CARE (PCC)?

It is easy to recognize what it isn’t, but what is it? And that’s been a huge challenge. And there’s been many reports over many years. The first report that calls for more person-centred care that I have found was published already in the 1930s. Here is a report from the Health Foundation in the U.K., where they say that there is no single agreed definition of the concept. And this is still an emerging and evolving area. So we can easily recognize what person-centred care isn’t, but recognizing what it is is still difficult. I like this definition that’s recently been published by the American Geriatrics Society Expert panel, which has two points to it. It is one point says what person-centred care is, and the second point says something about how to achieve person-centred care:

Patient-Centred Care means that individuals’ values and preferences are elicited and once expressed, guide all aspects of their health care, supporting their realistic health and life goals.

So person-centred care here is identified as exploring values and preferences and sticking to those as a guideline for our care decisions. And then how do we achieve that? And here they give us this advice:

Person-centred care is achieved through dynamic relationships among individuals.

So it’s a team effort here. It’s the patient and it’s the professionals. And there are also others that are important to them and they collaborate to make informed, shared decisions making to the extent that the individual desires. So shared decision-making is also a key term here in our work on person-centred care in the group.

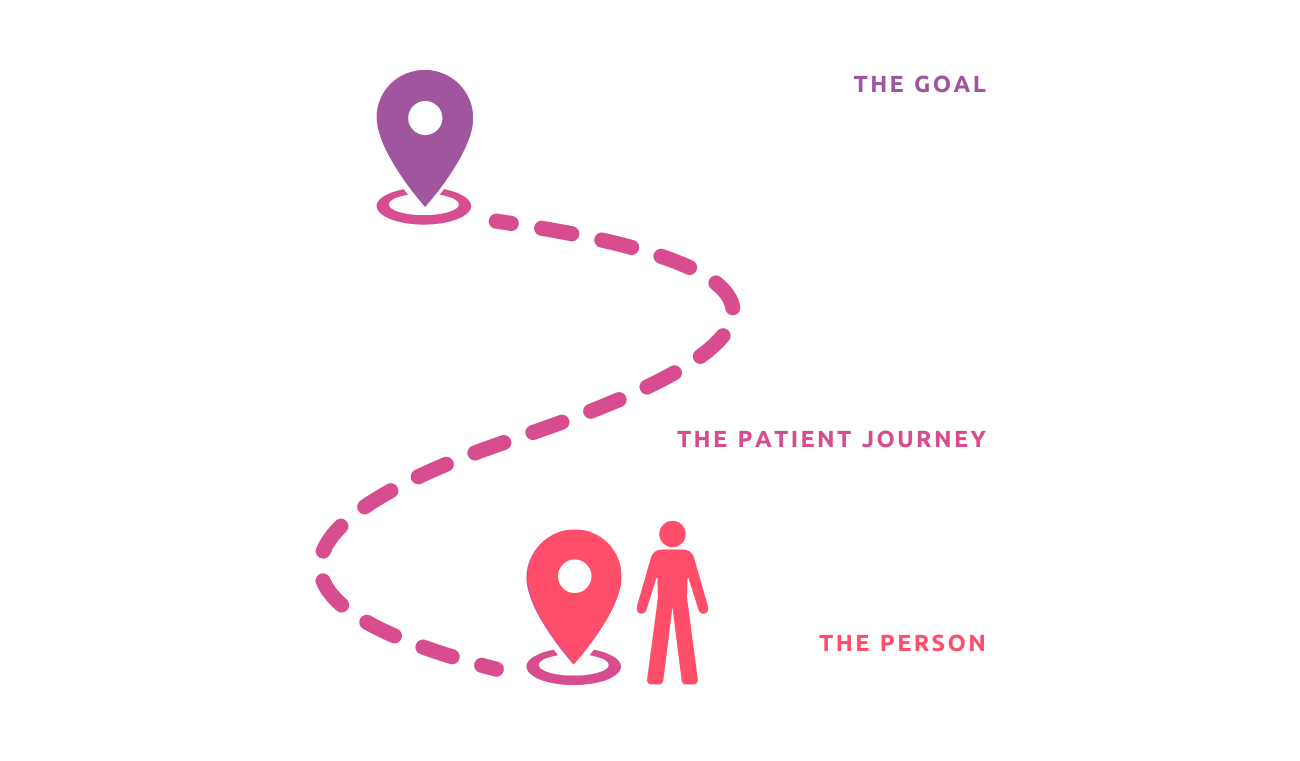

Every patient is a person who has a background, and that background and their life context define what was their striving to reach in their lives, and what matters to them. And if they have a health challenge that is a threat to that goal, then the patient journey is the way the patient together with the health care system, gets to work towards that goal. What matters do so in our having this picture of the patient journey and the patient’s life goal as the bigger framework. Health care’s role then is to support the person on their patient journey toward schools that are meaningful to the person. So with the picture in mind, our group has latched on to many of the same concepts that the American Geriatrics Society has, but we have emphasized the role of the patient journey. So to us and me, person-centred care is a sharing of power, so that the answer to what matters to you drives care decisions and patients and professionals who create the patient journey stay within the constraints set by the care system to reach those goals that are meaningful to the patient. So that’s what we think patient-centred care is.

The rhetoric for patient-centred care is very strong in most environments, there is no manager, no healthcare decision-maker, or no health professional that would ever say that I am not patient-centred.

We are all focused on and wish in the deepest of our being to support patients on their journeys towards better health. So this is a bit of a paradox if this is so important to us and it’s in every white paper, in every management document. And yet we have these reports from patients and we have these documentations that patients feel abused in our care systems. Why is this so? Why is person-centred care so difficult to achieve? If we don’t understand that, we won’t be able to succeed in strengthening person-centred care.

WE TEND TO BEHAVE IN ONE WITH THE SYSTEM GOAL

The answer to this paradox, I think, lies in this sentence here, because we tend to behave in line with the system’s goal. Now, what are our healthcare system goals? There is what we say the goal is, and then there is what our behaviour says the goal is. So let’s explore this a little bit further. What are what is the healthcare system’s goal? If we look at the W.H.O., the goal of healthcare systems is to improve the health of the population it serves. So that seems straightforward. But let’s look at the word health. What is health? So again, W.H.O., in my mind has done an excellent job here in defining health. They say that health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity. And then in 1986, they expanded this decision to say that health is their primary source of everyday life and not the objective of living in itself. And health is a positive concept, emphasizing social and personal resources as well as physical capacities. So there’s nothing in the definition of health care that constrains us only to deliver technically excellent care. The definition of health includes the life perspective that we saw also in the definitions of person-centred care. So that’s not the answer.

So but how does a care system improve health? Well, the micro-unit, the smallest unit where the care professional and the patient meet, is in the consultation. And in the consultation, there are two people, two people present. There’s a professional and there’s the patient. But I want to emphasize that even though there are only two people, there’s always a third party there, and that is the system.

The professional is always part of the care system in some way, and the care system consists of many frontline professionals and mid-level decision-makers and top-level national decision-makers. And the patient, if that patient has not, has a system he is a part of.

Most conditions today require maybe more than one meeting and often that patient then will meet with more than one representative of the care system. And there will be many professionals that meet the same patient. So the patient quickly understands and experiences that the consultation is maybe part of that journey, but it’s not the journey itself.

THE GOALS OF THE PERSONS:

- I own my body and my health

- I have a right and duty to take care of your “my health”

- I need support in taking on that role, within the context of my life and projects

THE GOALS OF THE SYSTEM AND PROFESSIONALS

- The technical excellence of care

- Cost-benefit ratio

- Defined by professionally define outcomes logic which does not include volatile, fluid and difficult-to-define personal preferences, values and needs

I like the quadruple aim outcomes for the patient is the patient experience and improved health information for the professionals. It’s professional satisfaction and for the care system payer. They’d like to see a good cost-benefit ratio, and I think that we can’t think of person-centred care without understanding this background here because of the three roles that are always present in every patient’s journey all matter. And each of the three roles the payer, the patient and the professionals, have slightly different goals in there on their way towards better health. The patient’s goal is clear. My health is a resource in my life. I want my health to support me, in whatever I want to achieve in my life. For the professionals, however, the goal is to serve and improve the health and function of our patients, and they’re not necessarily concerned with the life perspective and then the care systems where they are tasked with serving and maintaining and improving health at the population level and are perhaps the furthest removed from the life perspective of the patient. So here we have these three different goals that all impact what we’re doing while we’re providing care because the professionals are set in the context of the system and the system requires them to do and behave in certain ways.

So here there is the clash of two lines of logic. There’s the goal of the person, and there’s the goal of the system and the professionals in the system and the professionals. They want to see technical excellence in care. They want to see good cost-benefit ratios. They want to see outcomes that are defined by professionals.

And there is a logic here which does not include the volatile fluid and difficult-to-define preferred personal preferences and values and needs of patients. The patient, on the other hand, is the owner of their body and health, and they have a right and duty to take care of their health they need support in taking care of their health within their context and their life project. And these two ways of thinking don’t always meet in a good way. So my answer to why is person-centred care so difficult is that. Because patients are more fragile voices and because the patient voice has less power, it has less money behind it. We, as a system of players, pay more attention to the professional and system values than to the patient values.

So here’s a take on why it is so important also for the system to act and create a more person-centred care system. Because historically we’ve built healthcare systems to act on emergencies and in emergencies. The profession-centred, system-centred way of acting, where we act on behalf of the patient, where the patient is seen as a more passive recipient of care, is well part of the historic background that led us to the current health care design. But in the future the number of elderly, the number of patients with long-term healthcare needs will be growing. It is growing all over the world, both in developed and low and middle-income countries. And when your health care needs are long-term, it’s more the need to act together with the need to act in concert with the need to bring out the patient, resources become much stronger. So we’re moving away from a situation where emergencies are dominating our healthcare reality to a situation where long-term needs are much more important to be able to respond to. Populations are growing older, and this goes for all parts of the world. And in 2050, 10 to 30% of the Indian population will be over 60 years or older. And here are some statistics from India, which show the change in mortality and disability statistics from 2029 to 2019 over 20 years.

And you can see that all the neonatal disorders, diarrheal diseases, the lower respiratory infectious diseases are decreasing, whereas the increase is seen in heart disease, COPD, tuberculosis, and diabetes. These are long-term conditions where we have to work together with patients in order to achieve the results that we wish to see. And again, another statistic that is the same in every healthcare system that is being examined. If you look at healthcare spending and divide the population into three tiers, the 10% that spend the most funding the 10% health spenders they have, are characterized by chronic conditions, multimorbidity and a high mortality rate. And if you look at their costs, two-thirds of their costs go to this complex group. So the long-term health care conditions are going to be dominating our economy in our budgets, and we better get this right and do this the right way. And one of the ways in which we can reduce costs, and improve outcomes, is to work together with patients on how to improve their health. So sustainability is a huge component of why it’s important to work on person-centred care.

So if this is so important, then both at the system level and at the individual level, how can we change? And I don’t think we can answer that question without looking at the word complexity. Healthcare systems are complex, and understanding complexity is central to what we have to do. There is no simple fix to changing our way of behaviour.

So very briefly, I’ll run you through complexity theory. A simple problem is one where the cause and effect are well known and there is no discussion about what to do. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A patient in the case of a heart attack is an example of a simple, close-causal relationship.

We know that if someone falls due to a heart attack, we start with CPR. The standardized pathway is an example of a complicated problem. It’s a problem where there are many decisions to be made, but they can be made if you know your field well and you know how to assess the issues that each decision point to. And there can be a standardized or a complicated issue. There can be guidelines that say that, if so, go in this direction, and if not so, then go in this other direction. So we get these complex design decision trees that guide us in how to care best in the best possible way for our patients know for complex challenges, you cannot create such a standardized pathway.

And a very good example of a complex challenge is childcare. And no one would try to create a standardized pathway for bringing up a child because what you have to do in a complex situation is understand what the problem is, and then you have to try different possible solutions and see what works. If a baby is crying, it might be hungry, it might have a full diaper. It might need and it might have a bellyache, it might be underslept. And you just have to try each of those solutions and see what brings you to the goal. And so in complex problem solving, you try to discover which road fits best with the goals that we are trying to reach. So it’s an iterative trial and trial buy and fail and try to choose your path forward by the trial and fail procedures. And then the last part of the complexity theory is chaos and chaos. All rules are off the law is a typical example of chaos. And hopefully, we’re never in chaos in health care, but maybe in catastrophes and big crises we do have chaos, but mostly I’m interested in the complex problem-solving scenario here. So bringing that with us in a complex system, the iceberg model kind of describes how what the drivers are behind the events that we see. So the iceberg model says that you have events and patterns, which is what we described at the beginning of this talk.

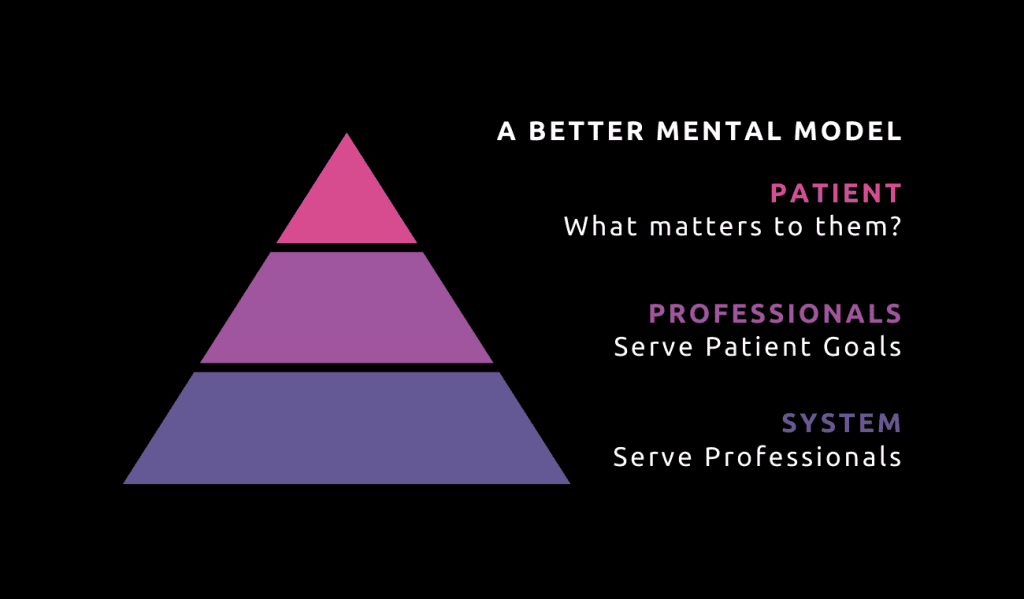

The drivers behind those patterns are the systemic structures and the mental models that we have of what we’re about. Then these elements, are stable, they’re interconnected, and they’re linked to a purpose slash function. To understand how to change our care system to be more person-centred, we have to work with these systemic structures and the mental models of our care systems. And this is where I go back to our three roles. Currently, we have a mental model where peer/governance and professional values dominate what we do. I’m not saying that we don’t ever listen to patients. I’m very clear that most professionals do it when they can, but then it’s not an “always” event. So what we want is to change this and make a hierarchy where the mental model is that the patient what matters to you is at the top of our goal hierarchy. Then the professionals – their role is to serve patient goals and the system’s role is to serve professionals in their capacity of serving patients.

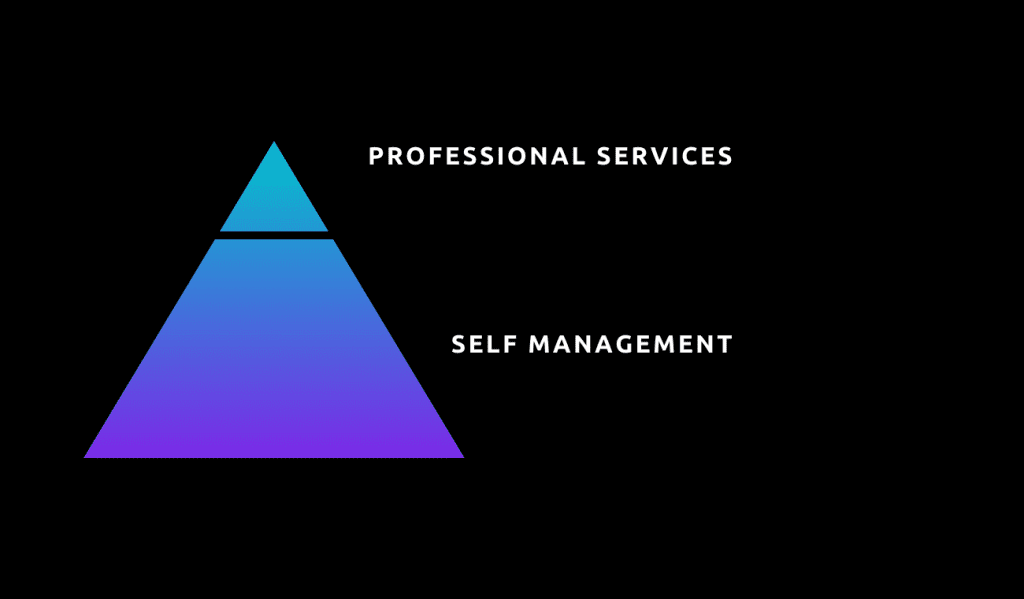

A NEW MENTAL MODEL OF PRIORITIES

Notice that what I’ve done here is not so much to change the system, but just to change the hierarchy between the goals of these three roles. And I’m saying explicitly that what matters to you in the patient role is what serves to guide us in everything we do. So how do we get there that it’s changing the mental model is not done at the moment? I think that we have to work explicitly in

changing our language and making the goal of the patient quite explicit and visible in our care system. So a new language is paramount. We need to document and we need to make information flow that makes the new mental model tangible. So in the new mental model, we need to understand who is the person. We need to document more of what, who, the identity of that person and how whatever health challenge they have and how affects that person. We need to document what matters to that person and translate that into goals for care. And then our role in the patient journey is to help the patient get to the goal and know a patient is an active person. The patient is the traveller. Professionals are our travel agents. We tailor the journey to the traveller and we try to make the journey meaningful, feasible, and as comfortable as possible. And in order to do this, we need to do this better. We need new feedback loops. We need to check on our progress.

So that means registering and looking at how we record what matters? What is the goal? Did we meet that goal? If not, what can we learn from what’s been done and how can we change? And then for each episode of care, we need to look at how are we listening to our patients and are we achieving shared decision making? And that can only be observed if we ask our patients directly. And then, a patient journey is made up of many episodes, but there is a link between those episodes. So the series of events need to be looked to, looked at together as a journey. The gaps. And were there gaps? Were there discontinuities between events? Were there any challenging events or events that were contradictory?

I also want to underline that many of the definitions of person-centred care bring into the loop the need for integrated care. I want to make a distinction between person-centred care and integrated care. Person-centred care leads to integrated care, but they are not the same. So if you have one overarching goal which is defined by the person, that is a goal that all the health professionals across the different organizations and across different professions, it will have a coordinating effect on those professionals. So what matters to you and how to translate and translate that goal into sub-goals for each of the roles in a patient journey has the fact that it automatically integrates care towards the overarching goal. And also person-centred care is not the same as proactive care, but person-centred care leads to proactive care in the sense that the person has their own care. They’re the main agent of self-management and self-care and that is one of the main determinants of good outcomes.

So professional services support patients in their self-management, and self-management is always proactive, looking at what are the risk factors. Do we help patients work with their risk factors to get the best health and outcomes that they wish for themselves? So I wanted to go a little bit deeper because I’ve now gone through the concepts and the principles, and I wanted to give some tips for the measurement and documentation of patient-centred care. And this is a form that’s very, very simple that I think might help us to document what patients want from their health care systems and their patient journey. And it centres on the question of what matters.

That question is not a method, it’s a concept. There are many ways of asking this question, and patients often don’t have goals at the top of their minds. And you might want to reformulate what matters to you and to what do you see for yourself when you come back to your home. How did this happen? Start a conversation with the patient about their experience with their health care issues. This form asks the patient to outline what their health challenges are and how difficult it is for them in the current situation to achieve or overcome their health care challenge and try to measure how successful they are in meeting the health concerns the person themselves outline as the main issue.

Healthcare workers and social workers have to start with what matters, explore what matters, plan together with the patient, start doing what they have planned together, and then evaluate what did they achieve and then learn and develop and change.

And then finally, I want to underline that the patient narrative is also very useful. The narratives are particularly effective in raising issues relating to values, morals, and emotions that might not be accessible otherwise. And it’s also very useful in encouraging more person-centred awareness. And finally, stories will even create meaning through stories that link past, present and future in a way that tells us where we should be, where we are, and where we could be going. And I think that discussing stories with our patients would bring out to a much greater extent, the experience of being on that patient journey and then in turn allow us as professionals to meet them at a spot where they are.