Management of Risk in Healthcare

Read the Magazine in PDF

Abstract

A systemic approach to managing risk and safety in healthcare, presenting a portfolio approach to mix and match various interventions. It acknowledges the challenges and varying pressures faced by healthcare systems and discusses safety in different contexts. Local leaders can implement cost-effective safety measures by conducting a safety assessment or system diagnosis, highlighting common approaches such as incident analysis and process mapping. Once diagnosed, leaders can determine priorities and develop a portfolio of interventions, as demonstrated by examples from Kenya, including reliable vital sign monitoring and formalized task sharing.

Introduction

A portfolio-based strategy is proposed to supervise risk and safety in healthcare, categorizing and blending interventions. This approach considers insights from Professor Rene Amalberti and Professor Mike English’s research. It addresses challenges in diverse healthcare systems, from the UK to Kenya. Safety must be examined beyond hospitals, including individuals’ residences. Expanding the approach to encompass protection in various settings is crucial regarding the quality of care. This methodology ensures effective risk management in an ever-changing healthcare landscape.

Constant and changing threats to best practice

Healthcare faces common challenges worldwide, with studies revealing unsatisfactory care and operational issues. Vigilance is crucial for managing moment-to-moment risks while striving for long-term improvements.

Safety can be achieved through different approaches, depending on the setting and nature of the clinical work. Comparisons with aviation show effective risk mitigation through protocols and insulation from external pressures. Healthcare can adopt firefighting principles, managing risk through procedures, routines, and teamwork. Highly flexible techniques, as seen in deep-sea fishing, may be necessary in unstable environments with unique risks and no established guidelines. Healthcare systems like pharmacy and radiotherapy resemble aviation, while elective surgery and psychiatric treatment relate to team firefighting. Adaptable approaches are essential for perilous situations like infections or unexpected events. Safety must be tailored to each context, embracing individual abilities and resilience for effective risk management

Safety Strategies and Interventions

Interventions and safety strategies must also be chosen to suit the context. Safety strategies can be categorized into five comprehensive groups for specific situations, whether in surgery, primary care, or other settings.

These five categories can be broadly divided into two groups;

- The first two categories aim to optimize and improve the system as much as possible

- The remaining three categories are more focused on avoiding harm when care is at lower levels and in dangerous territory.

Each of these strategies serves a slightly different objective. Once we have a distinct comprehension of these five categories, we can investigate instances of how to choose and combine them and put them into practice.

- The first approach is to focus on improving the reliability of the clinical process and supporting all individuals involved in healthcare. This is the approach taken in most quality improvement interventions that use checklists, bundles, and similar approaches.

- The second methodology emphasizes supporting the entire healthcare system, including managers, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists, to ensure that the wider system works as well as possible. In advanced systems, automation, and decision support can assist, while team roles and responsibilities should be clear to avoid issues from unclear duties. Standardization and simplification are also vital to improving the system and streamlining complex procedures for better functionality.

- Risk control is the essence of the third approach, which is used a great deal in other industries but less in healthcare. This involves agreeing on limits on what people are allowed to do, where care is delivered, and under what circumstances. The aim is to place restrictions in order to make care as safe as possible for the patient. Examples are restricting who can deliver high-risk medication or agreeing not to begin a surgical procedure until all equipment is in place.

- The fourth approach involves monitoring and identifying potential problems and preparing for issues in advance. Lessons from fighter pilots and team training can be integrated into healthcare to anticipate and address problems efficiently.

- It’s essential to observe and speak about problems in a complex system. The fifth approach, called mitigation, offers support to patients, families, and caregivers after something has gone wrong. Taking care of those affected and providing training programs can prevent situations from worsening. Supporting patients in identifying hazards and handling problems is vital in this strategy.

Application to Global Health Priorities

In resource-limited settings like Kenya, implementing safety measures to improve healthcare can be challenging due to limited spending and a shortage of medical professionals. Despite the absence of safety specialists, local leaders must take the initiative to adopt cost-effective approaches to enhance patient safety. The findings and recommendations for achieving this are compiled in two papers titled “First, Do No Harm.” Accessible for download at a later time.

Study 1: The study “First do no harm: practitioners’ ability to ‘diagnose’ system weaknesses and improve safety is a critical initial step in improving care quality” focuses on enhancing patient safety in low-resource settings. It emphasizes diagnosing the entire healthcare system rather than targeting specific areas for improvement. The paper presents various methods, including incident analysis, to assess the intricate relationships within the system and identify weaknesses. It advocates for a shift from a blame culture to a focus on high standards of care and calls for teaching system diagnostic skills to healthcare workers. [2]

Study 2: The study “How to investigate and analyze clinical incidents: Clinical Risk Unit and Association of Litigation and Risk Management Protocol” examines errors and incidents in healthcare. It challenges the notion of attributing errors solely to human error and highlights the importance of investigating incidents to identify underlying system issues. The study emphasizes a more nuanced approach to incident analysis, considering factors like the working environment and overall corporate context. Despite this approach gaining acceptance, it is not yet widely implemented in actual incident inquiries.[3].

Process mapping is a valuable approach for diagnosing healthcare systems. For instance, in Kenya, it revealed shortcomings in the drug delivery and dispensing process, leading to repeated errors. Other techniques like observations and interviews can also be employed. The interventions implemented should align with the local setting’s needs and priorities, with the diagnosis carried out by those working in that environment. This approach avoids a one-size-fits-all global program and allows leaders to identify priorities and develop specific interventions accordingly.

Study 3: It aims to empower local leaders in low-resource settings to enhance patient safety through practical and cost-effective interventions. The “portfolio” approach involves prioritizing critical processes, reinforcing the care system, mitigating risks, and improving response to hazards. With sufficient support, local leaders can make significant safety improvements. Proficiency in safety and quality improvement should be a key component of senior clinical and management roles, with national professional organizations providing education and support to these leaders.[5].

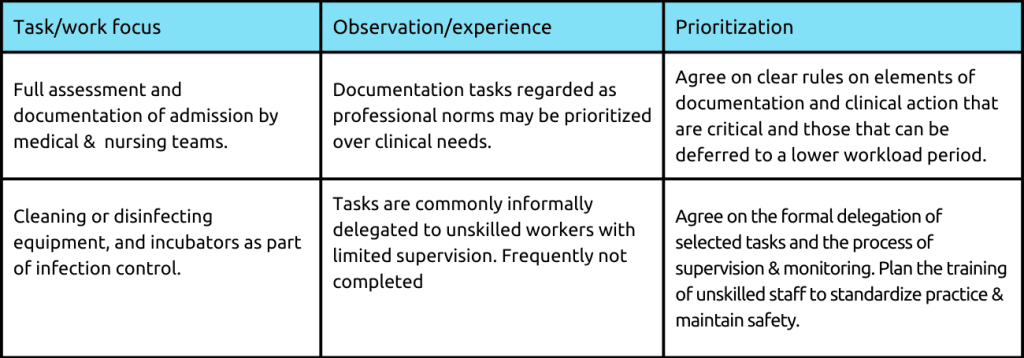

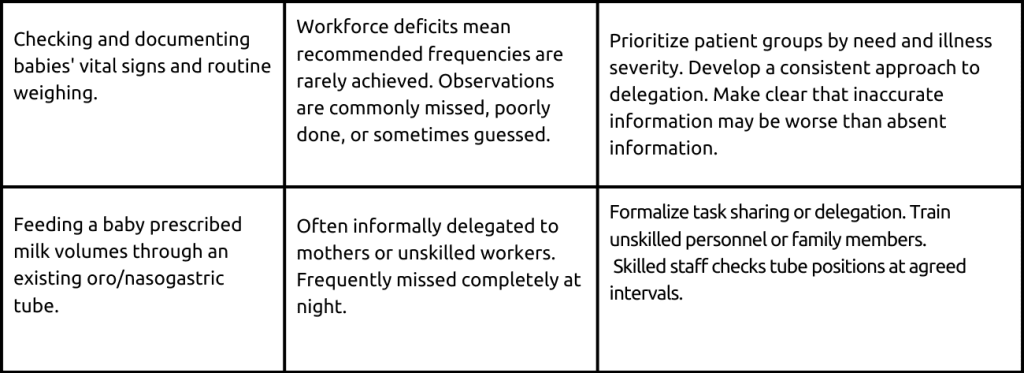

During an observation in Kenya, it was noted that some safety-critical procedures were not being given enough attention despite the presence of adequate staff and resources. To tackle this problem, they chose to give priority to certain processes, such as reviewing patient information during admission, ensuring proper cleaning and disinfection of equipment such as weighing scales and incubators, and guaranteeing dependable monitoring of vital signs. These procedures were identified as crucial areas needing improvement in routine care for babies, and addressing them could have a significant impact.

Safety Strategies

The Kenyan context provides examples of the different types of safety and quality strategies described above.

- The first safety strategy is focused on implementing best practices.

- The second strategy focuses on improving the organization of care, using methods like introducing whiteboards and combining handovers. These improvements can be made in any setting, tailored to specific needs and circumstances.

- The third strategy involves controlling risks, exemplified by the proper use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in Kenyan units. Managing risk includes making safe procedure decisions based on available staff and conditions, and setting limits on care to protect patients.

- The fourth strategy addresses hazards, emphasizing regular meetings to review and check on vital information, allowing concerns and issues to be expressed and shared among the healthcare team, similar to huddles in high-pressure settings.

Safety strategies can be applied in a wide range of contexts. The following is a summary of how these strategies can be employed:

1. Diagnose the system by evaluating strengths and weaknesses using techniques like process mapping, incident analysis, observations, and interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding.

2. Utilize a portfolio of interventions, combining various strategies like critical safety processes, best practices, organization of care, risk control, hazard response, and mitigation. Customize these approaches to address specific safety concerns in different situations, such as implementing whiteboards to improve care organization.

The general approach to safety strategies presented in this discussion can be useful in various healthcare settings.

By evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the system, healthcare facilities can foster a safety culture and enhance the quality of care they offer.

Conclusion

This systematic approach to risk and safety management in healthcare systems offers customizable interventions grouped into five categories. Examples from healthcare systems in Kenya demonstrate practical insights for local leaders to enhance safety cost-effectively. Prioritizing local needs is crucial, and the discussed papers provide valuable information for improving safety in any work environment. The vigilance of daily risks in healthcare remains essential, and this approach provides a valuable framework for enhancing safety.

References

- Shekelle, P. G., Pronovost, P. J., Wachter, R. M., McDonald, K. M., Schoelles, K., Dy, S. M., … & Walshe, K. (2013). The top patient safety strategies that can be encouraged for adoption now. Annals of internal medicine, 158(5_Part_2), 365-368.

- English, M., Ogola, M., Aluvaala, J., Gicheha, E., Irimu, G., McKnight, J., & Vincent, C. A. (2021). First do no harm: practitioners’ ability to ‘diagnose’system weaknesses and improve safety is a critical initial step in improving care quality. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 106(4), 326-332.

- Vincent, C., Taylor-Adams, S., Chapman, E. J., Hewett, D., Prior, S., Strange, P., & Tizzard, A. (2000). How to investigate and analyse clinical incidents: clinical risk unit and association of litigation and risk management protocol. Bmj, 320(7237), 777-781.

FAQs

Q.How can we mitigate the risk arising out of structural constraints in buildings like slippery floors, wet floors, in the bathroom, etc.? Is there any validated structure to address this issue?

A. The speaker, who is a psychology professor, admits that he does not have enough knowledge to answer this question. However, he suggests consulting an architect, as there is literature on the importance of design in safety. He also suggests that there might be a structure available, but he is not aware of it.

Q.How should we make more experts in the healthcare field for quality improvement and risk management?

A. The speaker believes that collaboration with other industries, more education in medical and nursing schools, and short courses on these topics for medical and nursing staff would help make more experts in healthcare for quality improvement and risk management. He also suggests that techniques that are fairly straightforward to understand and do not require a lot of money should be explored.

Q.How can we make the end-user more aware of quality healthcare systems?

A. The speaker suggests that patients and families are already aware of quality healthcare systems and that they should be enlisted to help redesign the system. He also suggests that patients and their families must always say if they think something is wrong and be made partners in redesigning the system.