Coproducing healthcare services

Read as Magazine PDF

How might we improve the value of the contribution that health care service makes to health? That question is what has led me to open this idea of co-producing health care services.

We need to:

- Recognize the difference between the logic of making a healthcare “product” and of making a healthcare “service”.

- Recognize the importance of the lived reality of the “patient person” and the “professional person” in a service that is co-created.

- Recognize how science informs the practice of co-produced health care services.

- Recognize how work habits and/or a work setting might limit the ability to gain insight into what’s important to patient persons who are historically underserved.

We are learning that though we weren't ready for this, we have been (or are being) readied by it. - Amanda Gorman

Indeed COVID has connected us all in a pragmatic tutorial and co-production. We have learned, as we are being readied that:

- new and useful scientific knowledge is only partly RCT (Randomized Control Trial) based

- there is a limited social understanding of how science builds knowledge

- professionals alone cannot eradicate the health problem

- contextual forces like judges and politicians have become de facto public health officials, not always for the better.

- we have seen this personal and public health schism that exists.

- health inequities are everywhere we look

- we confuse role and identity, and progressively exhausted professionals are either heroes or sometimes enemies.

- our information age includes misinformation and disinformation

- we are kin persons as one human to another as we face this challenge of COVID

- change can come more rapidly than we thought it could

- when people work together, they need respect, trust, shared learning and a sense of control

- innovation and constructivism and reserves or a little extra capability are both imperative and foundational and so much more.

HISTORY OF THE CONCEPT OF COPRODUCTION

QUALITY 1.0

Standards, Inspection, Certification, Guidelines

Looking back about 100 years or so, a group of surgeons asked the question, how do we recognize a good hospital? And that led to the standards of the American Board of Surgery and the Hospital Association. With their question came the recognition of and focus on this idea of a threshold. What is the threshold for becoming a good hospital or a good health care service?

And the initial focus was on big issues. But as time has gone on, some of those big issues have gone away. And we are now focused on peripheral or less critical issues, like did you fill out the right form? And it drives people crazy in some ways.

QUALITY 2.0

Systems, Processes, Reliability, Customer-supplier, Performance measurement

About 40 years ago, we recognized that gains in quality and safety and value were occurring in other economic sectors at rates of change that were much better than we were able to do in health care. And that led to a similar focus on enterprise-wide systems in health care for Best Disease Management. And we learned more about systems and processes and reliability and customer-supplier relationships and performance measurement.

QUALITY 3.0

Service-making logic, Ownership of “health”, Kinship of co-producing persons, Integration of multiple knowledge systems, and value-creating architecture.

About ten or 15 years ago, the question changed from how might we use enterprise-wide systems for best disease management to something like:

How might we improve the value of the contribution that health care service makes to health?

There is a difference between service-making and product-making logic. If we think about it, professionals don’t own the health of another human being. Health is owned by the person whose health it is. We are invited to think about new ways of creating the architecture of value in healthcare service. The ideal combination is 1.0 plus 2.0 plus 3.0.

3.0 ushered in a change of thinking on the basic formula for improvement:

FROM

Generalizable, science-informed practice in context, leading to measurable improvement.

TO

Some combination of patient aim and generalizable science-informed practice in context leads to measurable improvement.

It takes two parties to make a service. - Victor Fuchs

We have taken the idea of product-making, and we have used that to make a service. And then we’ve put all kinds of adjectives around that, like patient-centred or patient-focused. But underneath we have used the logic of product-making. Doctors make the service and sell it or give it or find some way to convey it to somebody else.

Carl Gersuny and his colleagues in the book and the Service Society were the first to use the term “Coproduction”.

They had read what Victor Fuchs had written and they said, “Two people making the same thing. There’s co-producing going on.”

Elinor Ostrom took that same insight with her husband, Vincent, and they talked about the co-production of public service.

And for that, she won the Nobel Prize in 2009.

Two people in the service marketing world – Robert Losh and Stephen Vargo said actually product-dominant logic had taken over our ways of thinking about making services and it has distorted the entire field of service marketing.

So what is a health care service?

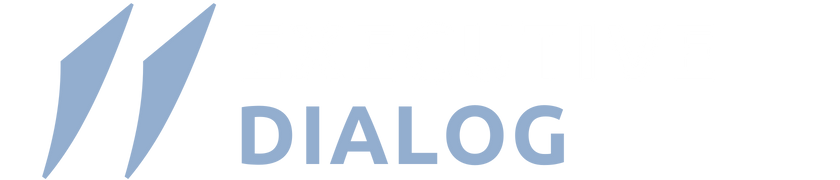

There is always a relationship and some action that were two parts of a health care service. And these two parts were held together by knowledge and skill and habit, a shared power, a willingness to be all vulnerable, and a mutual engagement in the process. But always lurking in the background was this power relationship that existed and that sometimes tended to distort the health care service.

It made me reflect on the ways that we had thought about a healthcare service when we worked to improve it. And what we had done in the name of improvement was to focus on the action. As if, the entire relationship and circumstance and action didn’t somehow come together.

It is never free of the dynamics and hierarchies associated with power. But I believe that underneath this that there is an ancient wisdom that is actually at work. Our kinship relation to one another lives in the ancient Hindu traditional knowledge of

Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam,

and in Ubuntu and other ancient sources of wisdom.

What were the drivers that made co-producing healthcare services possible?

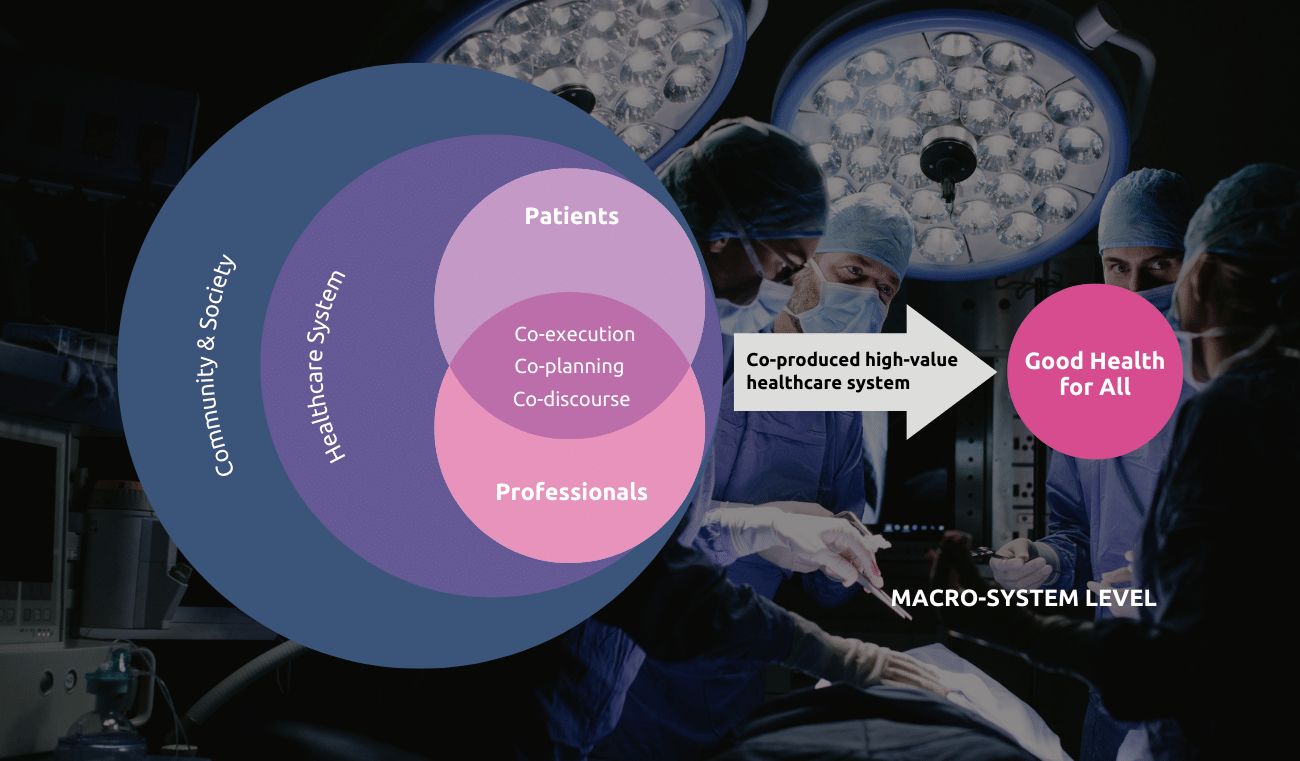

And it seemed to me that there were knowledge streams related to the patient person and to the professional person and their lived realities, the social supports that they enjoyed and the resources that they had access to. And the third stream was the knowledge of the as-is system. It’s the journey to be navigated and the emotions associated with navigating that journey. It’s the experience of when systems are both working and not working. And the fourth stream is science-informed practice. It’s not just the science of the disease or the condition, but it’s the science of the illness experience. And it’s the science of this services design that also is involved in co-producing.

And what helped me think about the inclusion of the professional person was the work of John Ballard and his team in the UK in this marvellous book, Intelligent Kindness. They suggest that there are two lenses in the glasses that we might use. One lens focuses on our kinship with one another, and the other lens focuses on the task. And together, it seems to me that these glasses allow us to begin to discover the service-making logic that is involved in braiding together these four streams of knowledge, skill and habit.

As I’ve explored the daily work of co-producing healthcare services, I have observed that:

- both relationship and activity are regularly at work, even though we don’t always honour relationships as we focus on activity in the name of quality

- knowledge, skill, habit and vulnerability are all connectors to bring together relationships and activity

- science informs our knowledge of disease biology is different from the science that informs our understanding of illness experience and the science that informs service design and redesign

- not only health but also learning are nearly impossible to outsource

- service-dominant logic offers us so much that we need to explore as professionals interested in trying to make better quality health care.

- these lenses of task and kin allow us to see things that we haven’t seen before there is a difference between role and person, and we would do well to figure out a way to remember both as we go forward health care service is almost always a combination of things that people do for themselves, plus the support that professionals might offer, and these systems that professionals help design and set up have to function in a way that they provide that support for self-care

- some of what we do, we think we know because of what we’ve learned, even though what we’ve learned might now need to be unlearned.

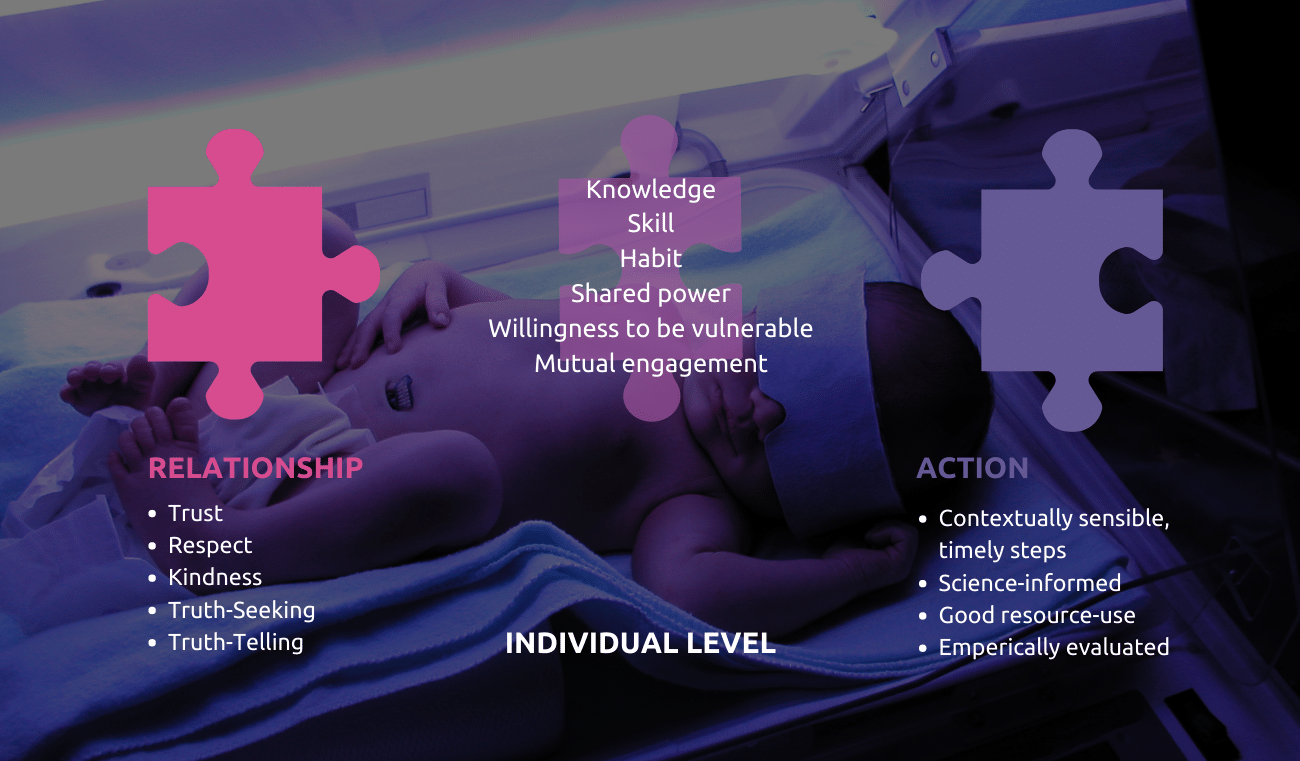

Oystein and his colleagues suggested that if we want to improve services, we need to be thinking about a different architecture of the systems than the architecture for systems of production. He said that there’s a different architecture for solving problems and making products, and the architecture of the systems for solving problems can occur at an individual level and a population level. A shop, as he called it, and a network where we’re responding at scale for a population. And that the logic or the architecture of the systems that help us solve problems is different from the logic or the architecture of making products like a value chain where we have a standardized sequential process.

Solve Problems:

- Value Shop – Customized response to a particular need

- Value Network – Responding at scale for a population

Make Products:

- Value Chain – Standardized sequential processes

I suddenly realized that number one was an example of a value shop and individual dyadic kind of thing. And this network, the whole read box, was for working with a population at scale for dialysis services. And within this, at a granular level, are things that resemble making a product like putting a needle into a vein or hooking that patient person up to a machine. So I began to see that what Oystein and his colleagues were talking about was possible to use in health care.

So I’ve come to understand that there are some implications of this health care service co-producing where:

- health is not outsourceable, even to prepared professionals, where

- professional preparation and practice, education, design system, leadership development, and integrative thinking are all at work.

- And that clinical practice knowledge, just like in genomics, can occur both in large groups and in small and based learning systems.

- Safety might involve the patient and family roles for safety or health care services, because it may just be that Charles Vincent and Renee Albert are right when they said that health care service safety is not a binary phenomenon. It’s not that healthcare services are either safe or unsafe. We need to make them safer.

- registries that started as disease registers are now migrating to learning networks and teams of teams so that

- new approaches to value creation are available.

So how is service-making different from product-making?

When we adopted what Toyota did and what Toyota was doing and their workplace and what other kinds of product-making settings were doing, we could see that process happened before Process B, which happened before Process C, and they had to occur in that order. If we were going to make at all that the logic of making a product is so compelling. And I realized that as I tried to put that thinking to work and health care, I would come up with these difficult problems where it didn’t always work linearly. Sometimes we started to go from A to B, but then C happened before we finished B, and then sometimes people entered B, not A. And so I realized that my linear frame of thinking about this was not the way it worked.

I started to have conversations with patients persons about these steps, what they called B, step B was not the same thing I called it. And so professional terms for thinking about these things were not the same as patient-per-person terms for these things. And I realized that a flow diagram of steps A, step B, and Step C had contributions along the way that we’re more than one party making the contributions. I began to realize that there was a contra at step there was a contribution that patient persons made and professional persons made, but we weren’t in the habit as professionals of acknowledging that as we were going forward.

Different from what I was in the habit of creating as a product design system. And so then this idea of trying to wear a pair of glasses that had one lens focused on kin and all the differences that exist among those people

that we simply sometimes call the patient actually would have different resources, would have different questions, would have different sources of support that exist. We want to impose simplifying ideas and the work that we do in order to make it understandable. But sometimes those efforts hide the reality that we, in fact, must address.

So I’ve begun to understand that this service-making opportunity is an opportunity for inquiry and for new methods and new approaches to the improvement of health care service and offers a lot of possibilities.

What themes of knowledge, skill, and habit help co-produce a healthcare service?

My sense is that there are at least these four maybe there are many more. But in my thinking about it, if we think about the stream of knowledge and skill that are involved in understanding the lived reality of the person we sometimes call a patient or the lived reality of the person we sometimes call a professional. We begin to see so many more so many possibilities. Such a small part of a patient person’s life is spent in the presence of a professional person. And we have made the assumption that the rest of that life somehow takes care of itself and is unrelated to better health. I don’t think so. I think actually that the whole person brings an opportunity for better health, that we have the opportunity to recognize and pay attention to.

Questions to Ponder:

- How is service-making different from product-making?

- How our relationships are important to health? And is this new knowledge?

- How are the scientific methods similar or different for building:

- knowledge of diseases or conditions or

- knowledge of the experience of being ill or having a condition or

- the knowledge of the design and assessment of a healthcare service?

- What are the streams of knowledge, skill and habit that help co-produce a healthcare service?

- And when have you experienced the co-production of a health care service?

Author

-

Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice